V – When Randy Started Over (in a Smaller Car)

A Story for Anxious Times

Chapter 5

There are almost no limits to the good God can do with an ordinary man who will trust Him. A man who will obey Jesus and ignore all the clamoring plans of his old heart. And so we are a clogged toilet away from the day Randy saved Jesse Henderson’s life.

He loved Margaret, still did even to the day he unlocked his brother-in-law’s coffee shop for a suicidal man in a suit. C.S. Lewis said that divorce is more like having both of your legs cut off than dissolving a business contract. And he was right, which is why Randy left Omaha. He confessed all of his sin to Margaret, his lovelessness, refusing to care for her and think about her and ask how she was doing and do anything especially affectionate for her for years. He did it in person and in writing, and he asked for her forgiveness. Other than signatures, the only words he wrote on any divorce papers, once she got through to him that there was no way she would stay married to him, were two words at the bottom of the last page, where there was some white space where he could fit them: “She’s right.”

After a hundred hours of conversation with Jerry and five times that in prayer (there were eight or ten nights that summer where Randy prayed through the entire night, pacing in the guest bedroom or laying facedown on the shallow office carpet in there, sometimes falling asleep after sunrise, going about the next day tired and feeling strange but also invigorated, sort of how he’d feel after a wrestling match in high school), he decided to let her have the house, and to never second guess himself on that decision or to think about it ever again. He broke that informal covenant a handful of times, but only once for more than a minute. And in general his new life began to be characterized by an almost complete lack of bitterness. The big guy game show host charm was totally gone, and in its place began to grow a hopeful, warm, joy that attracted people to him in smaller numbers but with vastly more substantial results (and more loyalty) than his old plastic confidence. Like Jerry, he was almost instantly a phenomenal listener, intently focusing on the words and the person who was talking to him.

Margaret noticed all of this, even as their lives began to sever, but she absolutely refused to attribute anything to it other than Randy’s not wanting the financial loss (and perhaps a few other losses he’d now finally counted up) involved in their divorce. His not wanting the house was one that was difficult to understand from that purely natural worldview, but eventually she just decided that whether he didn’t like the house or was just attempting a Hail Mary (Margaret knew football, one of the many things that had initially captivated Randy, years earlier) to win her back, it didn’t ultimately matter. She hated him and would not stay married to him, and there was nothing that would change those variables in the equation.

The week Randy left Omaha was hard. There was no coming back from that decision, and he knew it. There would be no being married to Margaret again, apart from some true unforeseen miracle. And he was leaving the man who had honestly become his best friend in just a few months. The only true Christian in his everyday life. To a lesser extent he was also sad and a bit scared of leaving his career, the only one he’d ever been excellent at (he’d sold 18 cars that last month, putting him in third at the dealership and making hotshot Mark begrudgingly ask him what it would take to get him to reconsider relocating).

The last time he ever saw Jerry face-to-face was at a Starbucks down the street from their dealership. They were sitting outside even though it was the height of summer, because Randy had wanted to. And since there was a wonderful breeze it was actually a good day for it, despite the fact that the table they were at didn’t have an umbrella. They both had coffee with cream and sugar, Jerry’s third of the day, Randy’s second. They each would have preferred cheeseburgers, but first one thing and then another had led them to Starbucks (the one thing being Randy’s tighter budget, the another being Jerry’s sense that they’d want to linger and that Starbucks might lend itself more to two hours of conversation with some long silences filled by people-watching in between goodbyes).

Jerry’s short, neatly parted gray hair rustled a little each time the breeze picked up. Randy couldn’t make out his kind green eyes as well because of the way the summer sun was reflecting off his glasses. But he did see that he never stopped smiling, really.

Jerry was sad to lose his friend, his little brother in Christ, his only truly Christian coworker at the car dealership (or at least among the sales staff). He would be lonelier at work for a season, but before he let self-pity gather in his heart he scattered it with thoughts of Joey, a young new salesman he’d talk to about Jesus in the next few days, Lord willing. He remembered God’s words to the Apostle Paul about the Mediterranean city of Corinth: “I have many people in this city.” Amen, Lord, he thought, and looked up at Randy as he began to tell him about his brother-in-law Bo’s house in Cincinnati.

“He’s such a generous guy,” Randy said, obviously still touched by his wife’s husband’s offer to let Randy move in with them and their family and work at a coffee shop he owned. Not for the first time Jerry noticed Randy looked younger. He still had grays mixed into his thick, otherwise jet black hair, and they were showing in the beard that he had begun to grow, too. But he smiled wider, now, and it was also quite obviously no longer a calculated effort meant to win something from you. Randy’s big smile was now a simple token of true warmth. And even though Randy had always had darker skin (they’d never talked about it, but he was one-half Sicilian), he was even tanner, now, because he’d taken up running as a way to think and pray and do something productive when he wasn’t working, instead of his prior pastimes of anger boxing, television, and the occasional joint). And he was funnier, now. Disarmingly funny. Non-sarcastic laughter, laughter with innocent sparks in the eyes, full-smiled good humor, makes a man look ten years younger and fifty pounds happier. Such was Randy. Thoroughly changed Randy. Soon-to-be-missed Randy.

“I’m sorry, Jerry. I’m rambling.”

Jerry smiled and shrugged, which was his way of saying he wanted his friend to ramble. He wanted to savor it.

Randy’s sister had indeed married a generous man. He was a little older than Randy, in his early fifties, with a few more grays and a little more lower back pain (he would not be joining Randy for his morning runs, though they would play racquetball). At a glance you might think he was a nearly retired shoe salesman, or a newly retired government accountant. Something about his relaxed face gave you just a moment’s thought that he had been quietly defeated by an adulthood of utter boredom. But it took only a handful of words before you realized how wrong his face’s opinion of the rest of him was. He was an entrepreneur, and the kind that doesn’t show up on television. The closest literary example would be Fezziwig from Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” but in the real world there are thousands like him. But unfortunately movies and television always swing at least a few degrees left of the real world, and so Phil Washington wouldn’t have made a “compelling” figure in a drama about the American economy, which is to say that he was too responsible and generous with his wealth. He owned several businesses, but the one that Jesse Henderson found himself crying in front of two August thirteenths after Randy landed in Cincinnati was “Bo’s Coffee.” “Bo” was Phil’s nickname, picked up in his late twenties because of how many different business ventures he had his hands in (“Bo knows houses,” “Bo knows dry cleaning,” “Bo knows travel agency-ing,” which was actually one of his two business failures, but at the time was the one that made him giggle the most), and Randy though he had never met anyone in his life more worthy of a nickname. Not that “Bo” in particular struck Randy as being a phenomenal nickname, though he liked Bo Jackson and the American spirit of adventurous effort as much as the typical next guy. It was that nicknames were supposed to be labels given from a place of endearment, and Randy had never met anyone more endearing than Bo.

He was kindness from strength, which is difficult to explain until you’re sitting across from it at its dining room table, ready to take your things up to a bedroom it’s giving you free of charge, but first eating a sugar cookie from a plate full it made especially for the occasion of you showing up emptyhanded and needing a family. Randy had had some experience with the sort of friends who offered what they knew they couldn’t give, collecting moral points for an offer that couldn’t be accepted because it wasn’t a genuine offer. What he’d had next to no experience with was an offer of assistance from a man who very much intended to give it, and give it cheerfully. And the most startling example came on his first night in Cincinnati.

Randy had pulled up in his nine-year-old Honda Civic, having had to sell his two-year-old SUV his last week in Nebraska, smiling because he was happy despite his pride, which never goes away this side of the grave. He carried a plastic Kroger bag with his toothbrush, toothpaste, deodorant, small NIV Bible, notebook, and night clothes in it. The rest was in boxes in his backseat. As he walked up the driveway with the nice looking outdoor in-ground lights and noticed the simple, calming stone fountain in the front yard, his sister had already seen him from the big dining room window and come running to meet him at the front door. It was such a beautiful and tasteful house and Bo was such a decent man that Randy had to will himself to remember that he wasn’t technically home. This was only temporary. But by then his sister was opening the front door and wrapping him in a huge hug, and Bo was gently smiling behind her and waiting for his chance. And Randy decided that for whatever home meant for now, he was home.

When they’d sat around the big dining room table, just to the right of their big, open kitchen with black marble countertops, Randy walked them through everything as he ate his sugar cookie. His failures as a husband, how Jerry had explained to him the Gospel the day they’d been at the hospital with his broken hand, how right there in the hospital God had given him a new heart and he instantly treasured and trusted Jesus, then about finding the divorce papers that afternoon, and the last few months as the divorce ran alongside his new faith, unable to sabotage it (because God is kind), but still hurting Randy more than anything ever had. They listened, his sister and Bo, saying almost nothing for the first half hour. But then Randy had mentioned the alimony check he’d need to send Margaret, and that he’d looked for some construction jobs online to supplement the coffee shop job. And Bo simply lifted both his hands off the table and mildly shook his calm face (looking as much retiring shoe salesman as ever) and said, “We’ve got it.”

Randy was totally confused. He hadn’t in the slightest expected what Bo was obviously (or at least Bo thought obviously) meaning, and so he first thought Bo hadn’t understood. For a moment, Randy actually second-guessed himself; is it called “alimony?” he thought. But then the truth occurred to him, and while he was grateful he wanted to give it back. “Bo, this is my mess. I’m the one who did this.”

“If being a Christian means anything,” Bo said, “it means helping somebody out of a mess he made.” And that was that. Randy looked down at the table, more than ever sure of who he wanted to become.

That night he sat outside on their porch swing, having just gotten his last box out of his backseat and into the spare bedroom they’d prepared for him. He needed some silence, which was medicine he’d never much taken before becoming a Christian. He was overwhelmed at how much his sin had undone his life. Omaha hadn’t been where he was raised, but he’d lived there almost fifteen years, and for all he’d known he’d die and be buried there, next to his funny and football-loving and gorgeous and decent wife. But life, friendships and marriage and house and home, had all been rusted out and had finally collapsed because of the slow, steady damage his selfishness and anger and clusters of other sins had wrought. So many failures and reckless decisions. I mean, he’d once bought a twenty thousand dollar boat on a whim. He didn’t even fish. Who does that? Lusting after other women, spending hours a day in front of the television screen, disregarding the law in his gambling and his smoking pot. Now he was a boarder in his sister’s house. Soon to have a teenager’s job while making alimony payments to the woman he loved but who no longer loved him.

And yet, clammy as his hands were as he weighed these things in his mind, he didn’t hate himself. Randy was still knee deep in grace, the magic that makes a man a Christian, and the smell and the taste of it, the sheer texture of what Jesus of Nazareth had done to rescue him from Hell, were still too new to him for despair to set in. And Randy had been dead long enough to know what he didn’t want to go back to. So he smiled, truly smiled, despite the reality of the pain he was in, and spun what his sister had given him in his hands as he gently swung in the dark.

She’d said she’d found it a few months back, and that was the extent of what she told him that night. There was more to the story, but something in her prevented her from telling him the rest then. Some secrets need to come out slowly.

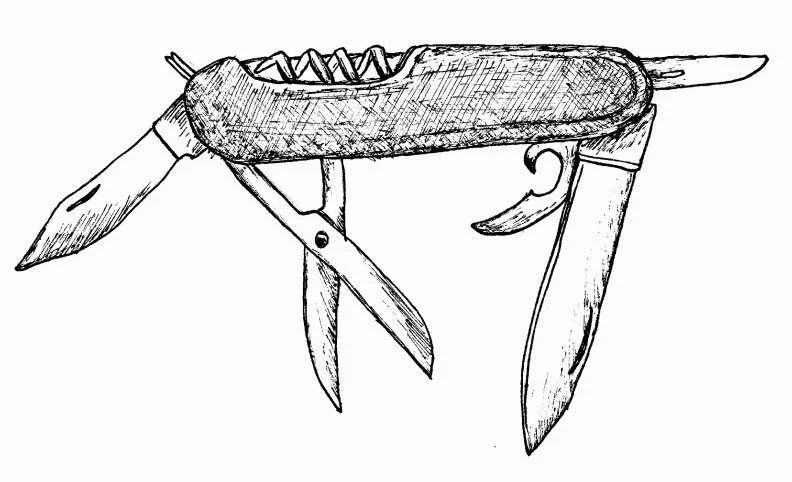

It was a maroon pocket knife. He unfolded the biggest blade, smiling as he watched the light from their in-ground fixtures and from the moon flicker of the surface of the metal, thinking about when he’d been ten or eleven and had carried it everywhere.

Linda was inside, pondering her brother, her God, her former sister-in-law, and her husband as she did the dishes. The part she didn’t tell Randy about that night a few months ago should wait.

And while she was wrong about that, it was still one of the most loving things she’d ever done for her brother.